A hundred years ago public interest in yacht racing was widespread and the press, both dailies and periodicals, printed long articles covering races in and off shore. People came to sit on the headlands and watched in their thousands as well. Offshore ocean races did not favor the picnicing crowd ashore and the tales needed to be told by the sailors. Ocean crossings in small boats and private races between big boats got wide coverage in the 19th century. In the early Twentieth Century periodicals like The Rudder and Yachting Monthly took the lead in sponsoring and promoting ocean races, starting with the Bermuda Race off the US east coast and the Fastnet Race starting at Cowes, England. The first three winners of the Fastnet Race were old boats of widely varying character and all three of these boats still exist 90 years later, all over 100 years old. Jolie Brise, 1925 winner as well as in 1929 and 1930, was built as a French pilot boat in 1913. Ilex, 1926 winner, was designed and built by Camper and Nicholson in 1899 as a yacht. Tally Ho, 1927 winner, was designed by Albert Strange in 1909 and built in 1910 as a cruiser from which the owner, a fishing fleet owner, could fish.

Jolie Brise was converted to a yacht in 1923 by E. G. Martin, one of the gentlemen who organized the first Fastnet Race. George Martin was on the committee that founded and organized the first Fastnet Race. Ilex, originally a cutter, was re-rigged as a gaff yawl in 1903, carrying this rig until made a gaff cutter in 1931, Bermudan in 1934. Ilex was purchased by the Royal Engineers Yacht Club in the winter of 1925-6 after their smaller Fulmar had finished second in the 1925 Fastnet. Tally Ho originally sailed with a modest cutter rig but by the mid-twenties carried a fidded topmast and full cutter rig with poled spinnaker. Tally Ho, originally Betty, sailed through the ‘20s under the ownership of Lord Stalbridge, Hugh Grosvenor. The 1928 Fastnet was won by the staysail schooner Nina, a purpose built ocean racer designed by W. Starling Burgess to win the 1928 trans Atlantic race to Santander, Spain which she did before winning the Fastnet a month later — sadly, Nina was lost with all hands in a storm off Australia in 2013. Jolie Brise won the next two Fastnets, after Nina’s, before a long line of purpose designed ocean racers took over starting with Olin Stevens’ Dorade in 1931.

1925

The first Fastnet Race developed from Weston Martyr’s experience in the 1924 Bermuda Race. The first Bermuda Race was in 1906 run by Thomas Fleming Day the founder and editor of The Rudder magazine, sailing from New York. After WWI, the Bermuda Race started anew in 1923 sailing from New London, Connecticut. After the 1924 Bermuda Race, Martyr wrote to Yachting Monthly extolling the ocean racing experience, which led to a meeting between Martyr, Yachting Monthly editor Malden Heckstall-Smith, and Jolie Brise owner E. G. Martin in which they decided to promote a race from the Isle of Wight around the Fastnet Rock southwest of Ireland, back to Plymouth. A notice of race was published in March and the race was held in August 1925, starting on Saturday the 15th.

The only full description of the 1925 Fastnet Race I know of is from the September 1925 Pickaxe, a Royal Engineer publication, described from their entry, Fulmar, a 41’ cutter from 1901 owned and sailed by the REYC since 1906. A September 2015 Classic Boat article on how Jolie Brise won the 1925 Fastnet Race describes extensive preparations from new sails to polished bottom but says little about the race beyond a mention of “Jolie Brise’s famous liveliness in light airs”. Yachting Monthly in October 1925 could do no better than say “It will be seen from the . . . corrected times, that the Jolie Brise won with comparative ease”. The Pickaxe account is quoted in Major General Sir Gerald Duke’s book, The History of the Royal Engineer Yacht Club.

The rules for the early Fastnet races called for starting East or West out of the Solent depending on the direction of tide and the Fastnet Rock rounding could be either port or starboard. The first three races started East around the Isle of Wight. The 1925 start was off Ryde on the NE corner of Wight in an Easterly breeze so the yachts could soon bear off to Bembridge Ledge off the easternmost point of the Isle, there to run off westward. 7 boats started, Gull crossed the line first followed close by Saladin, a converted Bristol Channel Pilot cutter, 49’ built in 1907, and Fulmar, then North Star, Jessie L, and Banba IV, Jolie Brise over the line last a minute and a half after Gull. The Classic Boat article says of Jolie Brise, “The Spinnaker was huge. On the first day of the Ocean Race it flabbergasted the other crews as Jolie Brise roared her way through the field after a cautious start.” In the Pickaxe telling, “After passing Bembridge Ledge, Gull drew ahead and Jolie Brise ran through the fleet to catch her up.” This was spinnaker work but it did not win the race there. Sunday morning off Start Point, Devon, Ilex and the leaders were moving slowly westward while Saladin had taken an offshore move finding a breeze to move out into the lead. Monday morning Saladin was out of sight of Fulmar as were Jessie L and North Star astern, Jolie Brise and Gull far ahead and Banba far astern. Fulmar’s crew watched Gull and Jolie Breeze sail out of sight. Past Lands End into the Irish Sea, Fulmar sat becalmed in fog much of Monday night but catching a lift at dawn she found herself sailing up to the other three leaders. As General Duke quotes the Pickaxe, “the four lay becalmed until the evening, when Jolie Brise ran right away from the middle of the fleet with a breeze of her own, leaving the other three becalmed for another night. It transpired later that Jolie Brise carried her wind all the way to the Fastnet, and this is what gave her the race.” That was Tuesday, Fulmar, Gull and Saladin still had much racing to come.

After drifting around together through the night and Wednesday morning they finally got a light breeze that built out of the west, driving the three boats to the Southwestern Irish coast where they tacked for Fastnet Rock. Gull, Fulmar and Saladin rounded the rock early Thursday morning, Gull being a mile ahead, the lighthouse keeper signaling that Jolie Breeze had rounded 12 hours earlier. After turning for home the wind increased so as Pickaxe says “the boats really got going for the first time in the race, and during the night had to shorten sail.” Friday morning Gull had extended her lead and Saladin was off to starboard, but in the afternoon the wind drove them north so they came on the Cornish coast north of Lands End. They had to beat through the night to make their Longships lighthouse rounding. Fulmar passed Gull and Saladin working to windward in the night, finishing first with Gull and Saladin following in that order, their handicaps not changing the order. North Star finished half a day later. Banba IV came in after the midnight time limit and Jessie L withdrew near the Fastnet, stopping in Ireland.

1926

Starting in the 1926 Fastnet Race was Ilex, the Royal Engineer’s new acquisition, and Jolie Brise, Gull, Saladin and Banba IV returning for the second edition. They were joined by Altair, listed as a cutter owned by Mrs. Aitken Dick (Altair didn’t finish, was listed as lost but found after search to have retired to an Irish port), Hallowe’en a newly built Fife cruiser-racer (maybe the first of the type), Primrose IV a 1923 50’ Alden schooner sailed from America for the Fastnet by Fredrick Ames (John Alden had won the 1923 Bermuda Race in his 47’ schooner, Malabar IV, and again in 1926 in 54’ Malabar VII), and 1901 Pemboch a 35’ Brittany built yawl, the smallest Fastnet competitor.

For the 1926 Fastnet I have General Duke’s telling out of the Ilex log, but also an article from The Rudder by Warwick Miller Tompkins who sailed the race in the Irish entry, Gull. General Duke begins thus: “The fleet experienced light variable winds most of the way to the Fastnet, with a lumpy and uncomfortable sea, but then a small deep depression brought strong south-westerlies, with rain squalls.Ilex rounded the Rock at 0830 on 17 August to learn that only Hallowe’en was ahead, and two hours later she passed Jolie Brise, still outward bound.” So, for the race to the Rock, detail comes from Warwick Tompkins in Gull. Starting off Cowes, not Ryde, further west in the Solent with a fair light wind, the yachts reached under spinnakers and for Primrose a square sail, out past Spithead to round No Man’s Fort into a freshening breeze. Here Hallowe’en took a southerly tack towards France while the rest beat their way along the Wight coast. Passing St Catherine’s Head, the southern tip on the Isle of Wight, with dusk coming on, Warwick Tompkins says, “Gull hit a soft spot and wallowed there as Saladin streaked past and Primrose, shoving her head into view once more, also went ahead. The last streak of lighted horizon showed Jolie Brise and Ilex far ahead, two tiny specks.”

Tomkins continues, “During the night Gull, utilizing a vagrant breath of land air, overtook Saladin and Primrose. In the early morning we glimpsed Halloween’s lofty Bermudian mainsail and Jolie Brise’s great jack-yarder far ahead. Ilex was gone. Then the day’s wind went to the southward, mist shut us in, and we left Saladin and Primrose far astern as we made our course. That night, Sunday, found us overhauling the leaders by the Start Light. There, to our disgust, the wind left us and we had the doubtful pleasure of again joining Saladin and Primrose as that choice pair ghosted up on a breeze that missed us utterly. On they came, the schooner astern doing best. Meanwhile Jolie Brise, caught by an in-sweeping tidal eddy, was apparently going backward into Start Bay, a manoeuver that delighted us until the same jocular eddy swept the big cutter to sea and a gentle zephyr that took her away on her course. Shortly after this we too got wind and sailed on, leaving Saladin doing the slatting act in the race and Primrose apparently badly off in the bight behind the headland.

“From then on we traveled alone. The Famous Eddystone light appeared ahead, drew abeam and was lost in the grayness astern. The wind stayed ahead, letting us sail a point or so free but persistently bringing weather such that oilskins were essential, and beneath them two or three sweaters.

“Monday, at one thirty P. M., we took our departure from Runnelstone Lightship just off Land’s End. A hundred and seventy-two miles northwest lay the Fastnet Light, and Gull, with a good wind filling every sail we could set, tore on across Bristol Channel, left England’s grayness for sunshine, logged a consistent eight knots, and sailed through a perfect, moonlit night.

“At eight thirty, Tuesday, we sighted brave little Ilex heading back on the home stretch. She was a long way off and bucking hard into the rising seas that were sliding us down their azure faces.

“A lavender mist was hiding us from the nearby Irish Coast when Jolie Brise passed us at a quarter to one, queerly shortened down to mainsail and jib. We wondered what had hurt her.

“Then the Fastnet loomed ahead and we doused the balloon jib, a wet job, and prepared for the sudden jibe around the lonely rock. The seas were big now, big but gentle to us as long as we ran with them and the slender Gull fairly ate up the few miles between us and the turning stake. Diminutive figures appeared on the high balcony above the rearing surf. Signal flags waved at us. We were too busy just then to heed them.”

Around, headed back, Warwick Tomkins again, “Then, braced against the rigging, I indulged in a semaphoric chat with the light keeper. Halloween, Ilex, and Jolie Brise had rounded, he told us, at one-thirty, eight-thirty, and

ten-thirty that morning. . . .

“Now we were smashing back against a head sea and a head wind, and we were getting no joy-ride. With the wind three points forward of the beam we slogged into great grey-backs, logging better than five nevertheless.

“Twelve miles and a half we battered on before sighting Saladin several miles to starboard. Fifteen minutes later Primrose, lugging all her balloon canvas, standing beautifully straight, and going like a race-horse, tore by within fifty yards of us, as lovely a sea-picture as I’ve ever seen.

“And now Gull, unfortunately has to pass out of this account.” Gull sprang a leak and the mainsail began to disintegrate in the heavy going so they headed for shelter in Ireland, pumping and bucketing through the night.

Meanwhile in the rising gale, Ilex was having her own adventure as told by General Duke from the Ilex log:

“We were racing again now all right, with no cruising inertia left. During the afternoon the wind freshened hourly, with some heavy rain squalls passing overhead. At 2030 sail was reduced to full main and jib, the jackyarder having been taken down during the afternoon. There was the devil in that jackyarder; I am quite convinced that it was only the firm statement by our topmast hand that if he had to stay aloft much longer he was going to be sick regardless of consequences that spurred the crew on deck to get it down at all. When darkness fell, both wind and sea were rising and soaking rain came down in the squalls. Nevertheless, though being driven hard, Ilex was behaving magnificently. By 2230 she had all she wanted and was bumping rather heavily at times.

“The wind becoming very strong, certainly gale force in the gusts, it was decided that she would move faster with a couple of reefs in the main. Accordingly she was hove to at 2330 and, like maggots from a cheese, the members of the REYC emerged on deck to reef. Reefing on a pitch dark night in a gale of wind is an exhilarating experience, certainly rather a novel one, which in the normal way one does not lay oneself open to. Coming from the warmth below into a solid sheet of rain and spray, with the shrill whine of a very strong wind in the rigging and the welter of the sea with phosphorescent breaking wavetops all round, was like coming into another world. Although the night was pitch dark there was no need for light. All that was necessary was supplied by the extraordinary phosphorescence of the breaking water. The reefing proceeded according to plan until nearly completed, when a sudden lurch and wave sent overboard a hand who was aft on the counter. The ship being stationary, he had no difficulty in hanging on to the rail. The skipper, who was at the tiller, saw his predicament, made a dive to haul him out, and slipped over the side as well. Momentarily sans helmsman, Ilex joined in the fun and stayed. The act of staying increased the midnight bathing party to three, a little variety being added by number three keeping hold of the main sheet instead of the rail. Much refreshed, the trio clambered on board again quite easily, and the matter of staying the ship once more was attended to. The inadvertent staying nearly cost us our topmast and mizzen, as it put the boom foul of the preventer and jumper stays. Fortunately the main sheet was hard in, thus preventing any damage.”

The press apparently got hold of the man overboard story, making much of it. The log goes on, “to be painfully truthful none of the ‘anxious comrades’ knew anything about the incident until it was casually mentioned over a tot of rum by one of the victims some half an hour later.

“At 0045 reefing was completed and the ship once more stood on her course, SE by S, with wind SSW and of unabated strength. Under the reduced canvas the ship was undoubtedly sailing faster than before, and riding the seas delightfully easily. We were now entering a steamer track and sighted one or two vessels crossing our path. The job of lookout forward with the heavy rain and sea and resultant poor visibility, was not an easy or a pleasant one, but all things come to an end and at 0315 the wind suddenly dropped, springing up again some ten minutes later from the SW and much moderated. The task of getting more canvas on the ship then began. Four a.m. saw the staysail set once more. By 0530 the reefs were shaken out, followed immediately by the setting of the mizzen and jib header. From dawn of the 18th to the finish we enjoyed a pleasant sailing breeze and bright sunshine, with a rapidly moderating sea. Every now and then came anxiety that the breeze would die away, but, thank goodness, it did not actually fail us. We made our landfall at 0830, Land’s End showing up four points off the port bow. The Wolf Rock was spotted on the starboard bow a quarter of an hour later. At 0910 the yankee jib was set, with the Longships abeam. The Runnelstone was passed at 1010 and a course laid for the Lizard with spinnaker set to starboard. A peaceful run, spent chiefly in drying clothes, took us to within sight of the Eddystone, when we gybed ship to fetch Plymouth.”

The Royal Engineers Yacht Club won the Fastnet on time. Halloween was in first, setting a record time not to be beaten for more than 40 years, but didn’t win. However, as the race was not over with 7 boats still on the course, I go back to Warwick Tompkins’ telling, he an American who loved seeing the Alden schooner do well:

“And now, with this demoniac night, Primrose — the dirty-weather prayers of her crew answered in full — behaved like a sea queen. Just as she reached the Fastnet her balloon jib carried away and hung itself on Cape Clear. Then her bully sailormen halted just long enough to throw a big reef in the main and another in the foresail. “now, lit-em blow off!” said young Ames, as he put her southeast on the trail of the vanished leaders.

“The weather had come late but it had come with a vengeance. A few miles ahead of the American, Saladin was having an increasingly hard time and there was a debate going on aboard her as to whether or not she could be hove-to. Further along Jolie Brise, staunch conqueror of Atlantic gales, victor in a thousand tussles with the Bay of Biscay, fought the gale until it screamed such a warning into the ears of her great captain that he reluctantly trimmed his sheets to windward, lashed the helm hard down, and waited for the fury to blow itself out.

“Spray shrouded the Primrose, rising ghostly over her weather rail and crashing to leeward in unbroken sheets, ringing a tattoo on oilskinned figures huddled in the cockpit and drumming on board-like sails.The mainmast, with the strain of the reefed sail at the middle, whipped like a poplar, and Ames, grimly hanging on to the wheel refused to go forward to look at his stick. He was afraid that he might be induced to heaving to if he saw how she was working. Foolish? you say? Ah! but the man who has the nerve to carry sail wins ocean races and the crew of Primrose had the rich traditions of sail-carrying clipper-ship sailors to uphold. How those old drivers of men and ships would have smiled this night!

“Once a great freighter, shipping the seas green over her fo’c’s’lehead, loomed out of the dark and passed astern while those on her bridge stared incredulously at the roaring schooner.

“Eleven o’clock — six bells by the cheerful ship’s bell — and Biddle crept to the taffrail to read the log. Ten and three-tenths knots the little ship was doing. For two hours now she had kept the pace. I have never heard of a boat with a forty-four foot waterline that went faster. Some while before the sudden calm that came at two in the morning Primrose shot past the struggling Saladin, leaving her miles astern, and showed the steady gleam of her running lights to Jolie Brise. “And now these three ships, shaking out their reefs, jogged on into Plymouth.

“Halloween and Ilex were there ahead of them. The big 12-meter owned and wonderfully sailed by Colonel Baxendale, had crossed the finish line Wednesday morning shortly after nine. Ilex, well within her rating, had breezed in twelve hours later. They lay there now waiting to see what challenger there would be to their pre-eminence.

“Jolie Brise stood in next, having made good use of the light winds she loves, and at four minutes past four she was swinging at anchor, glad of the shelter of Drake’s Island.

“The Royal Engineers were at breakfast when the jaunty Primrose slid into port, trimmed her white wings to the playful morning breeze, and crossed the line. The Engineers forthwith lost their appetites when their Skipper made a mistake, justifiable in view of his consternation, and announced that the Primrose had come within a minute of winning. A subsequent check of his figures altered his margin of victory to thirteen minutes and eight seconds whereat those sea-going Sappers — cheers for them! — breathed more easily. But gloom reigned on Halloween whose chances for second place were rudely crushed by the unexpected arrival of the

schooner.

“And, so far as Primrose IV is concerned, the Fastnet Race ended. Saladin, the gay comrade of the Yankee throughout the long grind, was next in, her crew yelling congratulations to the boat they had paced over so much of the course. And astern of this black cutter came that marvel of mechanical ingenuity, Banba IV, and tiny Penboch. But for the toughest sort of luck at the Fastnet when the latter’s debonair skipper had been unable to drive his Lilliputian craft around the rock, Penboch would have won.”

“It would be unjust to close this account without referring to the remarkably fine ratings worked out by major Heckstall-Smith. I would point out that every boat that finished did so within fifteen hours (corrected time) of the winner. That speaks for itself.” Warwick Miller Tompkins

1927

In the 1927 Fastnet Race the Royal Engineers again entered Ilex. General Duke’s short account begins thus: “The 1927 Fastnet Race was the first ‘classic’ race from the point of view of weather. It had been a wild summer, and on the evening before the race the committee were considering a postponement of the start the following morning. However the wind moderated and the 15 starters were sent off at 1130 on Saturday, 13 August. As the fleet beat down Channel the wind increased again, and by Monday morning was blowing a full gale from the west-north-west. During the next 24 hours, all the yachts but two were forced to retire.”

In Fore An’ Aft magazine there was an article by Peter Gerard (pen name of Dulcie Kennard who was married at the time or soon after to Maurice Griffiths, also aboard) sailing the race in Conor O’Brien’s Saoirse. Saoirse tried for three days before running back to Cowes in 10 hours. Her tale begins:

“The British ocean race for the Fastnet Cup from Cowes to the S.W. corner of Ireland and back to Plymouth was almost completely marred by bad weather. Only two boats out of fifteen starters succeeded in rounding the Fastnet Rock. These were the schooner La Goleta, 30 tons, and Tally Ho, the English cutter, 29 tons. La Goleta was the first to reach Plymouth on Friday August 19, seven days out from Cowes, and Tally Ho, about an hour later. She, however, was the winner on handicap having been allowed 8 hours, 55 minutes, 25 seconds. The two smallest competitors measured little more than thirty feet or twelve tons (Thames measurement), the largest being the 44-ton cutter Jolie Brise who won the first of these races held two years ago. Nicanor, the second American competitor, 36 tons, was among those forced by the weather to put back before getting out of the English Channel. Her crew said that they never encountered anything approaching such weather in all their twenty days out from Boston across the Atlantic in order to take part.

“What sort of a time they, and the other crews experienced in their individual efforts to lift the cup, no one can rightly know unless they elect to tell us, for within five hours after the start practically all the boats had lost sight of one another and necessarily remained wrapped in little worlds of their own for the remainder of the race. Let them speak!”

Fortunately, they did “speak” from the decks of the two boats that finished. Alfred Loomis described La Goleta’s race in his book Ocean Racing published in 1936. Lord Stalbridge’s account was published in Yachting Monthly.

Loomis on the race start: “In the morning the weather god, who has a sardonic humour, piped down the wind at the hour of the start, so that the postponement signal was not hoisted. We got under way in a moderate southwesterly, setting spinnakers for the run to the forts, and substituting them for reaching sails for the leg around the east end of the Wight. Then the wind began to blow.”

Stalbridge: “We got away with a good start from the line at Cowes under all plain sail and the jib topsail, but Jolie Brise, Nicanor and La Goleta soon passed us on the reach down to No Man’s Fort. It had been a dull, unpropitious morning and raining hard, and the wind was now gradually increasing into a good, stiff blow. We took in the jib topsail and ran close-hauled to Bembridge Ledge Buoy, but after rounding this mark the race resolved itself into a dead beat right away down till clear of the Sevenstone Lightship.” Sevenstones Lightship is past Lands End and 200 miles away, many miles beating into a gale! Only four boats got that far.

Loomis again: “Off St. Catherines it was blowing right pert. It was said that a sea swept us end to end, but that was before I staggered out. The fleet was scattering. Jolie Brise and Tally Ho were out ahead of us, and so was Nicanor. Saoirse, the ketch-schooner, whose name is Gaelic for freedom, was freely sagging off toward France. O’Brien had sailed her around the world, but he had never sailed her to the famous Rock in a Fastnet race. He never did. For three days he tacked forth and back across the Channel and then he upped his helm and returned to the Solent.

“For this was no race for semi-square-rigged boats. Nor for small yachts intended for sea-keeping rather than sea-going. Nor yet for yachts whose seams were soft and whose gear was aging. See how the list goes. Maitenes, Altair, Morwenna, Spica, Shira, Nelly, Penboch, Thalassa, and Ilex never reached the Lizard, and all put in to leeward ports.

Maitenes split her mainsail.

So did Altair.

Morwenna shifted a dinghy on deck which injured a man internally.

Spica’s bilge pump failed.

Shira couldn’t keep up with her leak.

Nelly and Pemboch, game little 12-tonners, wore out their game crews.

Thalassa blew out her headsails.

Ilex, the hard-driven yawl of the hard-driving Engineers, opened her seams in addition to blowing out her headsails.

“So, before the race is three days old, whom have we left in this jolly boating weather? Only Jolie Brise, Nicanor, Content, La Goleta, and Tally Ho. And still the wind god puffs his cheeks and blows down on the labouring fleet.”

Stalbridge, after the weathering of St. Catherine’s: “We now made a long leg of it into Christchurch Bay and fetched Poole Fairway by about 6:30 p.m. As the flood was against us, we short-tacked in shore down to Anvil Point and, keeping along the coast, weathered St Alban’s Head about midnight. Here we made a bad mistake as the wind had increased, and we decided to take in one reef in the mainsail, which lost us, of course, a certain amount of time. No sooner had we taken in the reef when the wind inclined to moderate, but as it was midnight we decided to let her run on during the middle watch under a reefed mainsail and a topsail, as we thought that if the wind increased we could easily get the topsail off her.

“It was now my watch below and, coming on deck at 4 a.m., I was pleased to find that we had weathered Portland Race and Portland Light was well abeam, so we shook out the reef and stood away on a long leg across the West Bay. By eight o’clock we were well across the bay and could make out the Jolie Brise close under the land off Teignmouth, with the Nicanor ahead of us and to windward. Ilex abeam of us and La Goleta on our weather quarter.

“All that afternoon we beat down under the land to Start Point which we weathered about 6 p.m. and then began a long series of tacks against the wind and tide to the Eddistone Lighthouse. At midnight we were some three miles to the east of the Eddistone and at 4 a.m., when I turned in, we were the same distance to the westward of it.

“We then made another long leg past Fowey and stood right into the land by Dodman’s Head. The wind by this time had got pretty well round to WNW and was blowing hard with fierce gusts, and we could just make out Jolie Brise some way ahead, nearly down to The Manacles. We tacked down under the land and off St. Anthony’s managed to get ahead of both Nicanor and Ilex; Spica, or at all events what we took to be Spica, and La Goleta were some little way astern. About 11a.m., just as we were approaching The Manacles, we saw a yacht ahead, evidently coming toward us, and as she approached, to our surprise it turned out to be the Jolie Brise. We could not think what had happened, but surmised that the weather was too much for her off the Lizard, and this proved to be correct, as she sailed close to us and when we asked her what it was like she said she had had to heave-to and that it was too bed. Now was our chance, as, knowing from the experiences in a gale in the Bay of Biscay what a wonderful sea-boat the Tally Ho was, and confident in our sails and gear, we thought that by reefing her down and making things ship-shape we might be able to weather the Lizard, and if so would catch the tide and be a tide ahead of any of our competitors who failed to do so.

“So we hove-to and double-reefed the mainsail, reefed the foresail and set our storm jib. We also got out the canvas covers for the skylights and the hatches and lashed them down securely, and put some more lashings on our dinghy and our spare spars and thus made ourselves as snug and as comfortable and watertight as we possibly could be. During the course of these operations Nicanor came alongside and spoke us and I told them what the Jolie Brise had told us. They apparently decided to run for the shelter of the land. Ilex, on the other hand, sailed past us into the foaming deep and would not wait to reef — a course of action we all greatly admired, but somewhat doubted the possibility of its success. A doubt which was soon afterwards confirmed, and we got a glimpse through the flying spray of Ilex running back under head-sails and mizen only.

“As we approached the Lizard we began to feel the full force of wind and sea and as we stood further out it was indeed enough to make you think. One big comber hit her and made her shiver throughout, sending a sheet of spray clean over the mainsail, but still she forged ahead and, choosing our time, we came about quite easily. Just after this I saw an extraordinary sight; a big oil tanker was steaming into it and as she lifted we could see her keel from forefoot to well abaft her foremast and then as she dipped, the propeller and practically the whole of her rudder came clear out of the water. This will give you some idea of the size of the sea that was running.

“We had to make two more tacks to weather the Lizard, but by 4 p.m. we had cleared it and were standing into Mount’s Bay. As we got nearer Penzance we felt the shelter of the land and the sea moderated, but the wind, on the other hand, appeared to increase in force and it worked round to the northwest. In the circumstances and in view of the fact that none of the others, as far as we could see, had rounded the Lizard, nor would be likely to round it that night, and also that we should have a foul tide and a head wind off the Longships, and that it would be folly to attempt to beat out there that night, as in all probability we should most certainly have had to heave-to and with the wind and tide against us would have drifted a long way back, I therefore decided to run into Newlyn Roadsteads and anchor until there was a chance of beating out round the Longships. I gave our sailor-men a night in while the amateurs stood anchor watches in the cabin: which, taken on the whole, was a far more comfortable and probably equally profitable way of spending the night than being hove-to off the Longships.

“At 6 a.m. the wind moderated a good deal and by 6:30 we were under way again,, but when we got down to the Longships there was still a big sea running. None of the other competitors was in sight and the question which exercised our minds was: could they have possibly passed us in the night or were we still well ahead? All that day we beat out into the Irish Channel, and by 10 p.m. we were about 6 miles north-west of the Sevenstones. The wind had now hauled round to the south-west and for the first time we could lay our course, with a nice sailing breeze and a fine night.”

“While Tally Ho was rounding the Lizard, anchoring for the night, Nicanor put in to Falmouth and La Goleta hove-to under the land all night. Alf Loomis continued his narrative: “In the morning we carried on. So in the afternoon did Nicanor, Simonds having ridden a bicycle down the headland until he could see for himself how bad it was. But she was now short-handed, and when her gaff broke midway to the Fastnet, discouragement overtook her and she definitely quit the race. That left three.

“Content, only nineteen tons, gave us the scare of our lives, as, on the evening of the forth day, we lay becalmed off the Runnelstone in a lull between two gales. She was only ten miles astern of us, and we allowed her twenty hours! But because of an error attributed to a faulty compass Content, whose owner was not aboard, made the coast of Ireland to leeward of the Old Head of Kinsale and withdrew at Cobh.

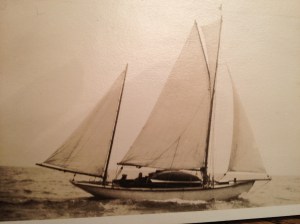

“So there were two of us — Tally Ho and La Goleta, as evenly matched as two boats of different rig and nationality can be. The cutter, a modified Falmouth quay punt, designed by Albert Strange, measured 44 feet, 3 inches w.l. The schooner’s like measurement was 39 feet. La Goleta’s overall length was 54 feet; Tally Ho’s was 47 feet, 7 inches. The beam of each was 12 feet and the drafts were nearly identical at 7 feet, 4 for the schooner and 7 feet, 6 for the cutter. With 1660 square feet of sail the cutter topped us only 110 feet. The one major difference — and that an eminently fair one under average conditions — was that La Goleta allowed Tally Ho 4 hours, 57 minutes for the course. But if it was anybody’s weather — which I doubt — it was Tally Ho’s.

“From the start as the field narrowed boat by boat these two had fought a dingdong battle. She walked away from us at St. Catherines and she again passed us at the Start, ourselves unaware of having led her in the interim. The night we hove to in the lee of the Lizard she lay snug at anchor in Newlyn around the head. In the middle of what is miscalled the Irish Channel we sighted her to weather and in six hours of sailing brought her abaft the beam. We had a fresh breeze from the southwest to take the place of the whole gale we had recently worn out, and we were making knots with all a schooner’s reaching canvas. Then with her squaresail [sic, no sign of squaresail or yard in Tally Ho pictures and likely confused with the big spinnaker] set, Tally Ho got a cutter’s breeze from nearly astern and walked away from us.”

Back to Lord Stalbridge as they reached across toward the Fastnet Rock: “At dawn the next morning we sighted a white Sail far astern, which we thought was Nicanor. By 3 p.m., favoured by this fine reaching wind all day, she was abeam of us. It was now a lovely day and perfect sailing conditions — a nice south-westerly breeze and a good long swell — but the glass was dropping fast, so evidently we had not yet finished with our bad weather. We got a sight this morning and a latitude at noon, but at 3 p.m. no more sights were possible, as it clouded over and came on to rain. By 6 p.m. we reckoned that the Fastnet bore north-half-east 11 miles, but as it was very thick and the visibility was scarcely two miles we decided to stand in slightly to the east so as to be sure of making the light.

“The schooner, in the meantime, had passed under out lee heading rather across our bows and was now to the westward of us. About this time she also must have come to the conclusion that the Fastnet was to the eastward of her, as she altered course and came in on the same course as ourselves, which put her about a mile astern of us.

“At 8.30 p.m. we reckoned that the light must be not more than three miles away, but so bad was the visibility that we could not even see the loom of any land. Just after this, however, we thought we could make out the loom of land straight ahead, and a few moments later the lighthouse lit up and there it was straight ahead of us, about three miles off. But by this time the wind had dropped to practically a calm and about 10 o’clock the American schooner came alongside and hailed us. To our surprise she proved t be La Goleta and not the Nicanor, so then we were practically certain that none of the others was ahead of us. We then got a puff of air and drifted ahead of her and rounded the Fastnet at 1.20 a.m., barely a quarter of a mile ahead of La Goleta.”

Loomis finishes the race from the Rock: “ We dropped into a barometric low near the Fastnet, breeder of future gales and cussedness accompanied by fog and calm. In stealthy rushes as vagrant airs picked us up we tracked down the light and sailed around it at midnight, Tally Ho in the lead. This would have been a good time for us to quit, for in the philosophy just quoted, the important part of the race was over and we must, as it were, start again with her full time allowance of five hours against us.

“But Lieutenant-Commander John Boyd, RN., my co-navigator, assured us when the wind struck in from the north-east that it never blew a gale from that direction in Irish waters. So there seemed little use of quitting. Two hours later when it was blowing a gale from that quarter and Boyd was laughing it off, and when La Goleta was down to her cabin house before we could yank a few rags off her it seemed like a good chance for sailing for Plymouth. We sailed. It blew Force 9 that night and pushed La Goleta along at six knots under foresail and forestaysail. But in the morning it moderated and backed, after some uncertainty, into the northwest. Then the wind slowly fell away to come in as a lovely sailing breeze at noon.

“We decked her out in cotton again and watched the wake snake out astern, swift and foam-flaked. Bill Tallman, shaved and brushed, fell overboard and was hauled back again, minus one boot but with an extinguished cigar in his mouth and an apologetic expression on his

cheerful face.

“In the afternoon we sighted and again overhauled our dogged competitor. She had made money when it blew sixty miles an hour and now we were taking it from her in a reaching breeze. We worked ahead under mainsail, balloon fisherman, and reaching jib, and at nightfall when the log showed ten knots and even more we carried this press of sail.

“Only the skipper, Boyd, and a young American named Marshall Rawle touched the wheel that night. There were six of us on deck, sitting alert to anticipate a call for all hands. We had to gain five hours on Tally Ho and there was no telling when either of us might be dismasted. At ten the ballon fisherman was taken in as Peverley blanketed it with the mainsail. Nine years have passed but I have not forgotten that next hour as we sat by watching wind, sea, and speed increase and attempted with delicacy to estimate the exact moment beyond which it would be humanly impossible to remain on the bowsprit while hanking the reaching jib. It was said that we bettered eleven knots in that hour, and while I doubt it now I was ready to believe it then.

“Oh, well. The reacher came in, and though they gnawed at our heels the seas swept nobody from the bowsprit — thanks chiefly to Pev’s masterly steering. And the forestaysail was set and we continued to make knots.

“Then in the middle watch we sighted Pendeen before picking up the Longships and as we were now running dead off we had to sail by the lee to clear the Runnelstone. It was my watch below after we had made certain of our landfall, and I don’t know how Pev did that job of steering. But I do know that I slept undisturbed and fitfully at five second intervals — content as we rolled to leeward and troubled as we invited a jibe with our alternate roll to weather.

“For all the blood we sweat that cold and wave-swept night, daylight showed us Tally Ho still in sight astern. So, mindful always that we were giving her five hours, or forty miles, that first sight of her squaresail (sic?) in the morning light marked the climax of the race. We averaged eight knots from the Runnelstone to the finish line north of Drakes Island, but we beat our sole remaining competitor by only forty-two minutes, and lost the race. Tally Ho’s corrected time was 5 days, 18 hours, 8 minutes.”

Lord Stalbridge’s telling of the passage from Fastnet to Plymouth: “The glass was now down to 29.3 and we were palpably in the center of a depression, large or small, of course we had no means of telling, but I fear that standing into a lee shore in thick weather and a falling glass was not an act of great seamanship. However you cannot make omelettes without breaking eggs; we were out to win the Fastnet Race if we could, so we were out to take some chances and luckily they came off as, no sooner were we clear of the Fastnet, than it began to blow hard for the north-east, and from 2 to 4 a.m. that morning I think we had as big a bucketing as at any time, as the wind was against the sea. Yet we had to drive her along for all we were worth, not only to beat La Goleta, but to get sea room. And drive her we did, more under water than over I fear, but by 4 a.m. it had got too bad and we had to heave-to and reef again. However we managed to jill her along and by 10 a.m. the wind had moderated and veered round to just west of north.

“We passed the Sevenstones at 4 a.m. and the Longships soon afterwards. Here we passed four or five French fishing vessels, all hove-to, and there was a really big following sea, which made steering anything but an easy job. However at 8.25 we made our number to the Lizard and hauled up for Ram Head. Under the lee of the land the sea moderated and we all had time to have a shave and a general clear-up before arriving at Plymouth. We set our jib topsail to help us in and crossed the finishing line some 50 minutes behind the American, but nearly 4 hours ahead of him on time. We lowered our sails and the King’s Harbour Master’s launch kindly towed us to our moorings on one of the Admiralty buoys, and then came a flood of congratulations and many hearty cheers from La Goleta’s gallant crew.”

Alfred Loomis gets in a last word: “This contest between Tally Ho and La Goleta was characterized at the time as the hardest fight between two yachts that had ever been sailed in English waters over so long a course and under such heavy weather conditions. As an epilogue I may say that certain journalists on both sides of the water were condemned for pointing out that while fifteen started all but two quit. We may have erred in our outspokenness. But we may have excited a keener appreciation of what ocean racing is. For in 1931, when they also had a heavy weather Fastnet, seventeen started and all but two finished.”

TODAY

Today Jolie Brise is owned by Dauntsey’s a co-educational boarding and day school in Wiltshire on the Salisbury Plain, UK, maintained and operated by the Dauntsey’s School Sailing Club. Dauntsey’s leased her from the Essex Maritime Museum from 1977 until 2003, when they offered to sell her to the school. In 2013 she sailed the Fastnet Race again with Club students as crew. The Dauntsey’s website contains this quote from Toby Marris, Dauntsey’s Head of Sailing: “Under Dauntsey’s, the boat has sailed approximately 175,000 nautical miles (three quarters of the distance to the moon) with 6,500 pupils as her bold crew.” As far as I can tell some repair and regular maintenance has kept her in sailing trim her 103 years. http://www.dauntseys.org/adventure/jolie-brise

Ilex was owned after 1971 by Salvadore Dali’s personal secretary. She was found in a sad state twenty years later in northeastern Spain by German Ruiz, her present owner, who acquired her from Mr Moore and then had her rebuilt, returning her to top condition and her original rig, gaff cutter. She is now sailing out of Palma, Majorca. There is a grand Youtube of Ilex sailing: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UHJ76nZ9Vqw

Tally Ho sits under cover in the Port of Brookings, Oregon, boat yard waiting for an interested party able to bring about her restoration. Through the 1950s into the 60s she was a family cruising boat out of the south of England. In the late 60s she was sailed to the Caribbean and then into the Pacific by a New Zealander. Damaged on and coming off a reef, she was rebuilt at Rarotonga. Brought to Hawaii she was bought by an Oregon fisherman in the early 1970s and fished the Pacific out of Brookings for twenty years before being abandoned there. Bought from the Port by a local craftsman, some restoration was done on her before he died unexpectedly. She is now the property of the Albert Strange Association

which has her listed for sale as a restoration project:

http://www.sandemanyachtcompany.co.uk/details/539/Albert-Strange-47-ft-Gaff-Cutter-1909/yacht-for-sale/

Acknowledgments

I could not have put together this account of the early Fastnet races without the help of the staff at the WoodenBoat magazine library who found for me the article by Warwick Miller Thompkins in the November 1926 The Rudder and in the October 1927 issue of Fore An’ Aft the article by Peter Gerard as well as M. Heckstall-Smith’s Outlook in the October 1925 Yachting Monthly recounting the early history of the Race. To find these articles Queene Foster had the pleasure of looking through their periodical collection filled with great stories.

Most important due to the apparent lack of other descriptions of the 1925 race was my contact with the Royal Engineer Yacht Club. Helen Stamp sent my request on to Andrew Douglas who kindly told me of Major General Sir Gerald Duke’s book, The History of the Royal Engineer Yacht Club, published by Geoffrey Tulett and Associates, Bob Lane, Twineham, West Sussex. I was fortunate enough to find a copy for sale.

The Lord Stalbridge and Alf Loomis articles are found in the Albert Strange Association Yearbook of 1980, found in Vol 1 of the collected ASA Yearbooks available through the ASA website, http://www.albertstrange.org/

c Thad Danielson

Jolie Brise, Rosenfeld Collection

Jolie Brise, Rosenfeld Collection

Ilex, 1927, Beken of Cowes

Tally Ho, 1927, Beken of Cowes